DESPERATE SELF

She only visits when it’s the middle of the night, two or three in the morning, and the baby won’t sleep for an hour or longer. She enters the room, assumes my position, and steals the baby from me. Angry, sweaty, monstrous, afraid. What can she do? Where can she go? Who will help her? No one. She lays the baby down, screaming. She takes three very deep, desperate breaths. She tries again, still desperate despite having done exactly what she ought to do. The baby still won’t sleep. Now the baby is probably scared of her because she’s not the baby’s mother anymore, she’s the Desperate Self. Two babies, now. The mother and the baby both have equal need. We forget this, our joint humanity. Of course the mother is responsible for the child — but she is still there, fully human just as the baby is. The Desperate Self roars her personhood. She hits a pillow with her fist. She tears the sweatshirt off her sweaty torso. She whisper-shouts curse words. She bounces the baby mechanically, resentfully, in a manner that certainly won’t soothe. The Desperate Self is making things worse, not better. Then, after some time, I am able to, gingerly, take the baby back from her. I coach him through it, apologize for handing him off to someone so wild. It’s just us, you and me. I tell him. I am doing my very best. Eventually, who knows why, he is able to fall asleep again. And the Desperate Self is gone, without a trace.

The above mini-essay, “Desperate Self” is an excerpt from a zine I published last year called A Year Postpartum. When I was writing the zine, I remember considering cutting this section. Do I really need to share this experience? Shouldn’t some things remain private? But something about it felt important to the piece, for one, and important to speak out loud, in an impulse of honesty, or confession maybe. To read it back again, it really isn’t admitting anything that bad — who hasn’t reached their limit with their child at some point, especially with sleep deprivation in the mix? But the hidden confession beneath the face-value of this piece is a more humbling one — until motherhood, I really had never encountered this part of myself, my “Desperate Self.” I have been shielded from desperation for so long. My childhood with loving parents. My marriage to a kind man. My whiteness, my middle-classness in a time of relative stability in America. My cis-straightness, my being so easily enfolded and accepted by cultural christianity throughout my childhood and beyond. My healthy children, uncomplicated births, my able and well body, relatively stable employment and ample support. The time and place and circumstances of my own particular life. All of these things have sheltered me from desperation for so long. But I do believe that desperation comes for us all, is inescapable to a certain extent. And when it comes, it changes you. To meet it now in motherhood, for the first time, within conditions that are still so gentle, so safe, has — shall we say — radicalized me. Maybe you can relate. Or, maybe you really can’t. All of those considerations, the degrees to which we have or haven’t truly experienced desperation, are maybe part of how we have gotten to where we are in the united states today.

It strikes me that my own Desperate Self is unruly. She misbehaves. She probably is not truly desperate at all, really, just exhausted, just angry. I still can’t understand what it would truly feel like to come up against true desperation. I don’t wish to know. I don’t wish for anyone to know. And, yet — I can’t help but think of mothers in Gaza, or any other crisis in which violence is everywhere and human rights have been abandoned. Yes, I don’t wish for anyone to know. My garden-variety gentle desperation is barely even related to that. But, still. It is real and it is new, a new experience for me. In motherhood, I have become acquainted with my own desperation. It is humbling. It is frightening. It is honest. And now, in the midst of the chaos we are feeling as the country is being jostled and threatened by the not-so-gentle hands of a new administration, I am feeling the echoes of new desperation rising in me — surprised by the wash of shame that almost always follows. In not knowing what will happen, and whether things will truly unravel in the way my mind has convinced me is possible, I am surprised and ashamed by how afraid I am, and how that fear is dominating some of my more virtuous traits. I am surprised that, like a frightened animal, I mostly want to run away.

I accidentally saw a video the other day where a tiktok psychic said with fervent certainty that there would be widespread and long-lasting power outages in March. I say accidentally because I’ve been intentionally avoiding my “For You Page” so that I don’t see anything like this. The way my whole body froze and my stomach dropped. I shifted from rational self to Desperate Self in an instant. Listen, I know that you can’t trust any old tiktok psychic! I know! I KNOW! But my body doesn’t know. My body, like that frightened animal, wanted to buy a generator immediately and burrow deeper into some safe bunker, as if we can make ourselves safe in one fell swoop. My body reacted, and my mind contracted, and my spirit — well my spirit is so exhausted that it is nearly ready to lay down and give up. If I am overreacting, so be it. I am excellent at catastrophizing. I’ve seen way too many terrifying projections into the future lately. Talk of collapse, of martial law, of huge unrest, of war. None of us actually know what will happen and we are all projecting that fear in a million directions. It is hard to find a way through all of that talk and I have let my mind entertain it far too much. As I articulated to my husband the other night, “I am so permeable!” I had never described myself to myself that way before. But it’s true. It’s what makes me a poet, I think, that permeability, the way life seeps into me and stays. But it makes it all so hard to bear sometimes.

Oh, friends, the way the ground underneath us was never solid but it used to feel a lot more solid than it does now. I realize that I am learning this late. So many people, more wise or more vulnerable, those who have lived through much more desperation than I have, have known all along and have told us repeatedly. It took me until now to really see the cracks. I’ll own the naivety that reveals. I’m trying very hard not to panic. But, really, panic is like a bruise. Most of the time it is better to ignore it and let it heal (if it can heal) — but sometimes it feels good to press right in the center, to feel the pain, to let it exist right at the center of your consciousness. To allow the fear some presence, some realness. And then to consider whether there is anything rational to be done.

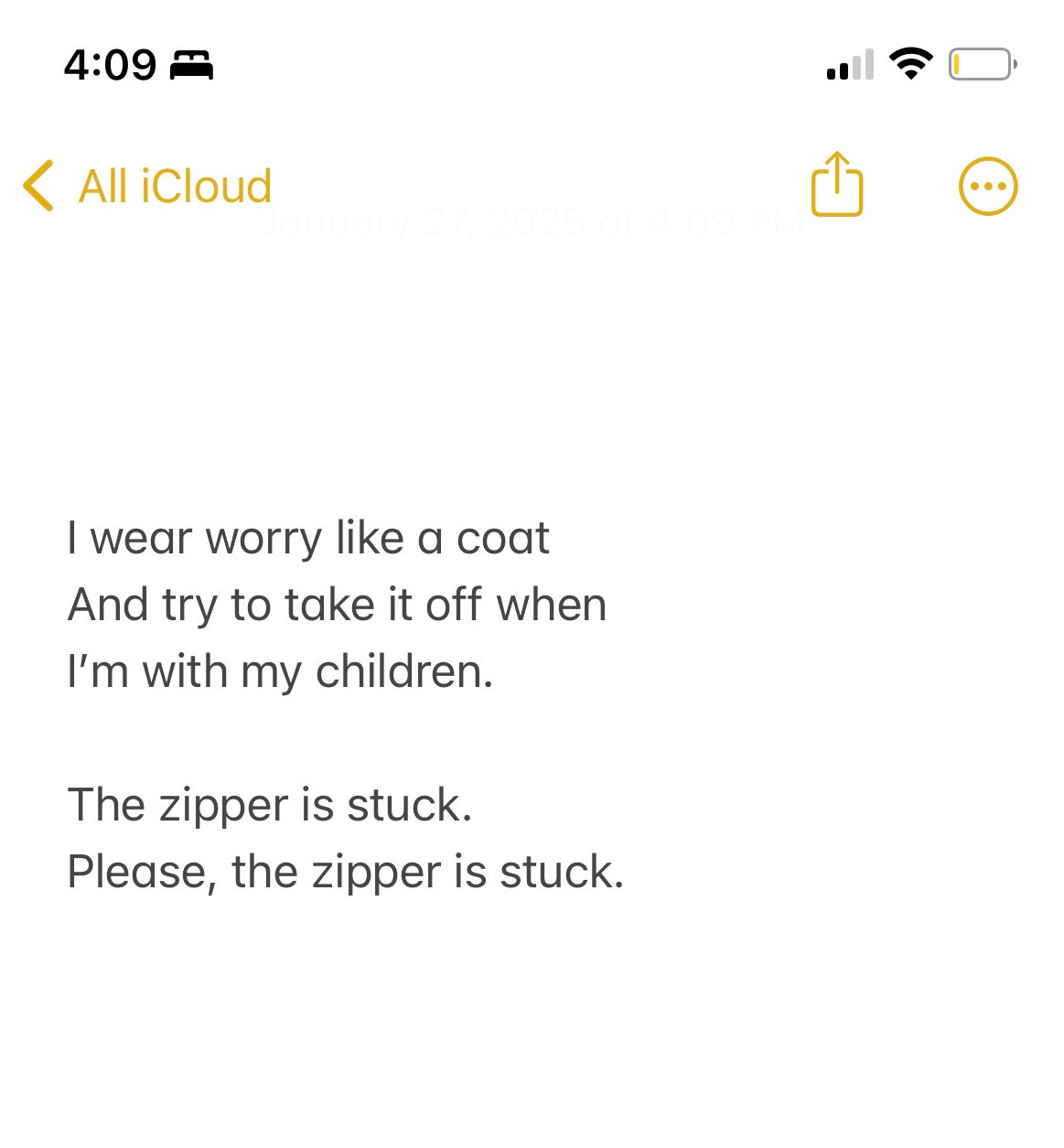

I know I’m not alone in this feeling. I know it because when I posted this poem on Substack notes, over 500 people liked it, which is a lot for substack.

The worry is hanging heavy on us, like a wet wool coat, and it really does feel stuck. It is all too much. Collective fear, collective heaviness, it’s weighing on everyone I know, especially the parents. There’s really something about loving a child that makes you suddenly feel everything in the world more viscerally. In my own experience, it’s almost like I didn’t quite live here before — I felt untouchable in a certain way. Now my skin is so in the game, because my children are here and they are depending on me and depending on all of us, and it is so uncomfortable, so truly frightening. I couldn’t access those stakes before. Now I can. The Desperate Self is alert. The Desperate Self is waiting.

I’ve been disappearing into novels, recently, reading at a faster pace than I have in years. A lot of this has to do with my youngest son getting a little older, old enough to play around with his brother while I sit nearby reading a paragraph or two before they need something. That’s a new development. But also I have a new capacity to focus, probably in a true reflex of self-recovery — my fractured mind that has been addicted to my phone’s instant gratification has finally hit a critical limit, and I want to throw my phone and its algorithms of misery down a deep dark well. In this moment, novels offers me a more rational escape from the fictional catastrophes my mind writes much more badly, or from the scary theories about collapse that the talking head voices would weave into my nightmares if I let them. I’ve been hearing lots of chatter about the novels that seems to have predicted our current or future state to varying shades and degrees: 1984, Parable of the Sower, The Handmaid’s Tale, etc. I know I can’t read those right now, that they would set me truly spiraling. But a few less trodden books have offered strange solace.

I read a book last month that, at first, I thought might be too upsetting to read in this moment. It’s called The Wall, by Marlen Haushofer. It’s an older book, published in 1963. In the book, an unnamed middle-aged woman is vacationing with her cousin and her cousin’s husband at their hunting lodge in the Alps when, overnight, she is cut off from the world and from all humans by an impenetrable invisible wall. All life on the other side of the wall appears to be frozen, or petrified, as if by some weapon of mass destruction. But the woman is alive behind the wall with only a dog, a cat, a cow, and the supplies in the hunting lodge. In other words — apocalypse, the likes of which I can’t imagine. But the book is stunningly hopeful, and in practice, is mostly descriptions of the physical realities of survival in the mountains behind the wall. The woman survives by planing potatoes and beans, by shooting deer, by milking her beloved cow. The animals become her family, and the woman’s mind somewhat clears and blossoms. I found it deeply comforting in the end, despite the brutality woven throughout. What comforted me was seeing the narrator encounter desperation the likes of which I hope to never encounter, and move beyond it, continue to live. The mundanity of the book, the beauty she uncovers in her life of hardship and solitude. In a way, the woman inhabits her Desperate Self, and then lets that self live freely. Something about that has felt like a helpful corrective to my more panicked impulses. The woman could not have prevented the wall. She did nothing to make it obliterate her world. To see her live beyond the wall’s cataclysm was a comfort and inspiration to me. And isn’t that what fiction offers — the chance to imagine beyond the limits of our own mind’s walls?

It makes me think of other books that I’ve read which have invoked desperation, survival. I don’t read them very often because I find desperate circumstances to be understandably upsetting. But The Vaster Wilds by Lauren Groff comes to mind. The main character in that book is running away from the Jamestown settlement early in America’s history. It is much more brutal, much more desperate than The Wall, and reading it really terrified me in quite a few ways — but it still left me with strange hopefulness. It’s that raw release of breath after the terrible thing has happened, life after the breaking point. The desperate self’s full expression, running at full speed away from the terror until it can’t run any more. Reading fiction like this allows me to exercise that muscle, the muscle that would and could run, the engine of fear inside of me. It reveals to me what I hope will never happen. It reveals humanity there too. We are alive until we die. I have to remind myself of that when I begin to imagine the worse.

I don’t wish to sound too grim — things are very bad, but all is not lost. I know this, and I remind myself repeatedly. But, like I called out earlier, sometimes the only way to get past the ache of fear is to push the bruise, to allow the pain to touch you instead of trying to ignore it. I felt this when I started a new book the other night, not knowing really anything about it. (TW for stillbirth, skip a few paragraphs ahead if you don’t wish tread there). The New Wilderness by Diane Cook opens with a stillbirth. The narrator, Bea, is alone in the wilderness as she gives birth to a baby who is early and dead. The scene is stunning because she is not afraid, she’s hardly grieved, she simply buries the baby and leaves the place behind, returning to her husband and older child without a word about what has just happened. I lay in bed, stunned, reading this scene, my own baby breathing deeply, asleep in the sidecar crib beside me.

The world of the novel is a terrifying one, where Bea and a group of others have come to live in a place called the Wilderness State to escape pollution in a futuristic overpopulated climate-change ravaged city that had left Bea’s older daughter critically sick. Her daughter is thriving in the wilderness, despite its brutality. But what really stunned me about Bea’s reaction to the stillbirth is her relief. She spells it out clearly — she does not want to raise this baby in that world, in the wilderness. She had come to the wilderness in the first place to save her child, and she could not be sure she could keep both children safe. To brush up against this maternal logic terrifies and resonates with me. The vulnerability of caring for children in even much safer chaos is frightening — let alone in a dystopian wilderness.

Who knows if I’ll finish this book, it has very mixed reviews, but the opening scene will stay with me. In this case, Bea’s desperate self said goodbye to her baby, knowing she was safer dead than alive. I shudder at that understanding, but I recognize it. It’s even biblical — calling out one of the most chilling passages in the entire bible, toward the end of Luke 23, starting at verse 28. “But Jesus, turning to them, said, “Daughters of Jerusalem, do not weep for Me, but weep for yourselves and for your children. For indeed the days are coming in which they will say, ‘Blessed are the barren, wombs that never bore, and breasts which never nursed!’ Then they will begin ‘to say to the mountains, “Fall on us!” and to the hills, “Cover us!” ’ For if they do these things in the green wood, what will be done in the dry?” Back when I was reading the Bible all the time, this passage always caught me and wouldn’t let me go. Weep for yourselves and for your children. Blessed are the wombs that never bore, the breasts which never nursed. This is probably the single most unsettling moment of the Bible for me, probably because of Jesus’ profound honesty, his unflinching admission that the world is not safe, not even for children or for mothers. That the world’s sickness runs deep and leaves all of us vulnerable. We have seen this in real life — how many children murdered in Gaza? And we pray that we will never live it ourselves, but who is to say that we won’t? I and many others in America, who have lived relatively comfortable lives, may be brushing up against this reality for the first time right now. Or maybe not. I don’t know how you feel, only how I do.

I want to be a person who can work for the good of all people, in good times and bad. To do that, especially in bad times, I need to face my own Desperate Self. I need to look her square in the eye, reckon with the rawness of my fear. Only after I am able to do that can I more bravely act toward the values I know I hold. For this and for so many other reasons, I am thankful for fiction, for the opportunity it can give us to brush up against our deepest fears and to imagine life beyond them. A way to feel the empathy for others’ desperation flow through our own mind’s echo-chamber. Reading desperation in fiction makes my own capacity for uncertainty feel just a little bit stretched, a little bit of needed expansion beyond my own borders. I think that is a helpful feeling for all of us right now, to put ourselves in someone else’s shoes, consider their fears and the lengths to which they will go to survive, their bravery, their defiance of desperation’s baser impulses. And, for that reason, I am reading as much fiction as I can get my hands on, especially now.

Oh, friends, I hope everything will be ok. I am keeping myself as sturdy and stable as I can for my kids as the ground shakes beneath my feet. This whole essay reveals how green and naïve I am, I’ll own that. I long for a world that is safe for everyone, knowing that that world does not exist. I long for it anyway. I conjure it into being. I create it with my own body, wrapped around my children, whatever comes my way. No desperation will change that. After the first fear wears off, the desperate self is strong.

These are the three books mentioned in this essay, and here’s a link where you can find and buy all three. Note that these are affiliate links, so I’ll be paid a little bit if you buy — but I encourage you to check them out from your local library if you’re so inclined! I am proud to be a library power-user, myself. :)

As always, I love to hear from you — please comment with any thoughts you have. And I always appreciate likes and restacks, sharing goes such a long way!

If you like this free newsletter, here are the best ways to support my work as a self-employed writer and artist who is also a full time caregiver:

SHARE WITH A FRIEND! It makes me so happy to hear when folks have sent my essays along to a friend who they know will resonate with it. That’s the best!

SHARE ON SOCIAL MEDIA! It helps! It really helps!

BUY MY ZINES! I’m really proud of my tiny publishing project, Imaginary Lake, and the zines I’m writing and hand-making. You can find them here. This is the best way to keep all of this going!

More soon, much love!

I read your paragraph about The Wall and thought “I bet she’d like The Vaster Wilds” before reading on. Hah. Have you read Station Eleven? I haven’t revisited in many years but it’s about making art after an apocalypse in a way I found to be deeply hopeful.

Thank you for sharing about your Desperate Self, especially in the form of an exhausted mom with a baby that won’t sleep. As a new mom myself, I have also encountered this same Desperate Self and am working through my shame and fear of her. It helps to see I’m not alone